Learning Frequencies

A learning and development company placing the whole person at the heart of change

Learning Frequencies

A learning and development company placing the whole person at the heart of change

Groundwork: why behaviour change alone isn’t enough

A familiar sound is reverberating through organisations today. Leaders are grappling with the culture change of our age; from centralised hierarchy, to collaborative ecosystems. The go-to solution that slips through conversation is ‘behaviour change’.

To this I’m inclined to say ‘stop’. Trying to change the behaviour of individuals is a piece, but it’s not the silver bullet to sustainable change. Behaviour and culture are talked about as the same thing. They are not. Some definitions:

Culture: the invisible DNA of values, beliefs and attitudes that hold a collective identity together

Behaviour: the visible result of the motives of an individual – observable actions driven by their values and beliefs

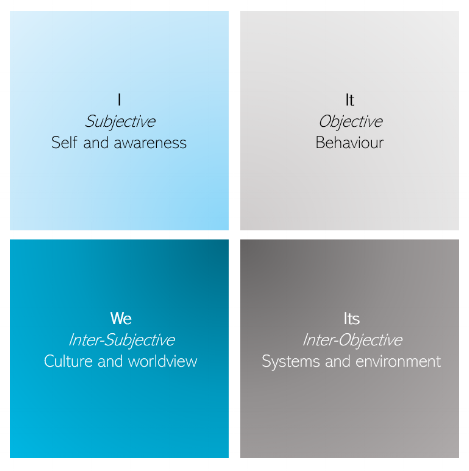

Philosopher Ken Wilber’s AQAL model helps to explain why behaviour change alone does not lead to culture change. Wilber explains there are four fundamental lenses we use to look at the world - ‘objective’ (thing), ‘subjective’ (person) and both of these in their respective plural forms. So that’s: ‘It’, ‘I’, ‘Its’ and ‘We’, make sense? Behaviour is an ‘It’, whereas culture falls into ‘We’. Behaviour plays out on the surface, whereas culture lives beneath the surface. All too often organisations use an ‘It’ lens to understand a ‘We’ domain of reality. A near miss.

AQAL model by Ken Wilber

If you’re looking to change culture, you might be tempted by a traditional recipe. Create a list of values and run a training programme to instill them into the way people work. Rate their performance at the end of the year to see what they need to achieve before promotion. It makes logical sense, but given people are more than logical, this can actually lead to more harm than good. Getting people to act on values that don’t come naturally to them, will likely result in the exact opposite of what you want to see.

What’s happening when people resist change?

When a vision for change is set not everyone is able to live up to it straight away. Under the new cultural narrative, vulnerabilities start to surface and people try to protect themselves from a sudden loss of status. They default to stonewalling any suggestion of change, and can start to behave in reactive ways. This was the case with an executive who, in the run up to a departmental meeting, was asked to engage with team development activities. While his team looked to him for direction on leading the event, he made a point that getting his attention during that phase was a privilege. He filled his diary with anything that took him away from the office. The team were left bemused as to why at such a crucial time he had distanced himself from the team.

To lift the lid on his behaviour, we turn to the seven levels model by Barrett Values Seven. Just like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the seven levels shows that human beings develop through stages of motivations - survival, belonging and self-worth for example. A key difference is the point of self-actualisation. In Maslow’s model this is seen as the peak of human potential. In the seven levels this is the point of transformation, where we go beyond our personal needs and become motivated to support the common good.

When an organisation tries to move from hierarchy to collaboration, levels beyond personal needs take precedent. It’s this that provokes the reaction. People grip more tightly to their motives, leading to an excessive focus on themselves, rather than the organisation’s purpose and mission. Whether they’re aware of it or not, this has an unhealthy ripple effect and limits the organisation’s potential.

Barrett Values Centre Seven Levels Model

Creating the conditions for change

What does all this mean for your culture change programme? It means you need to do the groundwork first. It means creating the conditions for openness, so that people can bridge differences when a new set of values comes in. As change specialist Nora Bateson says we need to “tend to the contextual capacity for those changes we would like to see”. And that means, if you really are going to do behaviour change, then focus on the way people relate to each other. Starting with you.

If you’re leading a culture change, your work is to influence and inspire people by the way you role model the collaborative culture you want to see. This means being equipped with particular ways of responding when resistance or tension arises. When people are confronted with a change that feels uncomfortable, they’re given a choice point. They could get caught in a stress reaction, or if they’re self-aware they might catch the discomfort, stay open and lean in to the challenge with curiosity. The latter leads to personal chance at the edge of their stretch zone.

Let’s imagine two colleagues disagreeing on how to pitch a product idea. Sarah wanted to deliver the presentation with lightness and humour. That was a jarring suggestion for her colleague Noah. He wanted to keep it focused and formal. Noah spotted his reaction before objecting, and considered how Sarah’s intention was to keep the stakeholders engaged. Having paused he gave a considered response: “These are really good ideas Sarah. We’ll just want them to know we’re clear and focused on results as well.”

This example points to ways we can self-regulate and respond creatively when differences in values come up:

1. Acceptance

During moments of tension, simply notice and accept what’s happening for you. ‘I’m having a reaction to Sarah’s suggestion. So it is.’ With acceptance you are acknowledging your reaction from a state of awareness. This is the opposite of bottling up your emotions, or trying to push them away.

2. Unconditional positive regard

Coined by humanist Carl Rogers, unconditional positive regard is to see the other person with total acceptance. This means looking past their attitude and behaviour to see the underlying intentions beneath.

3. Bracketing

Another Rogerian concept, bracketing involves acknowledging the needs and motives we have when tension arises, and setting them aside so we can attend to what’s most important right now, only to come back to those needs at a more appropriate time.

As simple principles of openness these help to keep people with different cultural maps moving in the same direction. But what if you’re on the receiving end of reactive behaviour? How can we take remedial action? This means (within reason) taking a u-turn on the common notion that there is wrong and right behaviour.

What difference can appreciation make?

For many of us it’s instinctive to see weaknesses as a problem, and we don’t like looking at the areas we need to develop. Comedian Dylan Moran summed up this attitude in his sketch on potential: “You should stay away from your potential… it’s like your bank balance: you always have much less than you think”.

It’s funny because it’s ironic. The truth is, every ‘weakness’ is a signpost to the area where our greatest potential for change lies. When an individual is over-controlling, we might read these behaviours as ‘bad’; we could condemn them, shame and blame them, or we can read them as a hot-spot of opportunity for change. Have you ever experienced someone respond to you from a position of appreciation? When people see weaknesses as an opportunity, culture starts to move. People start to engage with curiosity, asking ‘what needs to be addressed here?’ and ‘how can we progress this?’ Compare this to seeing their behaviour as a problem to fix or quash. In that case we’re working against the direction their energy wants to go in. To quote psychologist Marshall Rosenberg: “How do you do a don’t?” Instead, we can encourage them to channel their energy in a more positive direction.

A fourth principle of openness:

4. Appreciation

In those moments people try to block new cultural attitudes - moments of stonewalling, the warmth of an appreciative lens can ease the tension, and create a common ground for them to re-engage. This kind of attitude is twofold:

See the other person in the light of their highest potential, appreciating their resistance as an opportunity for growth

Look for where they already shine and describe how their strengths can contribute to the desired outcome

Simple principles of openness

What’s the impact on organisations?

In our experience, when people adopt these principles, the impact on both the individual and the organisation is palpable. They become engaged in their own growth, continuously developing every time they hit a hurdle. In the team environment there’s an uplift in motivation, and people’s commitment to results sharpen. They become ready to pick up more responsibilities, and to coach their colleagues as mutual partners. This all works to create momentum, as people commit to the purpose of the organisation with a level of responsible freedom and flow.

What we’re describing here could also pass as a description of a collaborative culture. In a hierarchy, the presence of a leader is what drives activity. But when people become aware, relational and purposeful in this way, everyone plays a part in leading. The energy of leadership unhooks itself from role, identity and status, and becomes a lived intention across the whole team. From one person to the next, energy is unlocked from the resistances that once gripped them, to create a positive movement, continually renewed by each individual. Organisations become leaderful.

When these breakthroughs occur, the very meaning of leadership shape-shifts from noun; a role or set of behaviours, to a verb; relating with presence to the here and now, as well as the common purpose between us. It’s developing the eye to see leadership in this way - the verb, which unlocks ingenuity in teams, and it’s this that we invite change leaders to bring into being. As Nora Bateson says:

- Nora Bateson